Recently, I came across the work of Dan Taeyoung. Taeyoung is a pretty interesting person, someone who is thinking a lot about how community functions in the 21st century. He’s worked to develop spaces that facilitate “inclusive and just” collaborations—in part inspired by a belief that “our friends and collaborators and our spaces” are a fundamental part of our cognition. Better spaces mean better collaborations, in Taeyoung’s view, and this ultimately leads to the capacity to think better thoughts and do better work. Toward this end he’s co-founded a nonprofit membership cooperative which is structured as an intentional community, and a project space “organized through collective decision-making processes.” He also helps to run an interdisciplinary browsing library containing over 1600 books from “various fields of inquiry” but with an overarching motive of producing “a generative approach to understanding how we are embedded in pervasive technological systems.” Once it’s safe to travel again I would love to visit:

Taeyoung was trained as an architect, and he teaches at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (I visited there in 2018, incidentally, to see this exhibition of materials from the collaborative team of two great visionaries, Arakawa and Madeline Gins). Despite being an architecture-school “insider,” Taeyoung is often critical of the ramifications of standard architecture pedagogy. All too often, Taeyoung argues, the teaching of architecture as a discipline serves to replicate the logic of the real estate market, yielding a system which functions as a “giant commodity fetishizaton of […] space,” wherein we “care about space based on how much a profit oriented market pays for it.” This system focuses “on newness and innovation […] as a method to have unique and desirable ‘products’ of space.”

Architectural schools that seek to put a gloss on this grim capitalist logic typically do so by implementing a “fine art” approach, which emphasizes the work and practices of superstar architects. But the focus on bankable personalities, in Taeyoung’s view, really just draws on the principles of a different market (the art market). Even if we delve further into the fine art approach, attempting to zero in on the pure aesthetics of space—“design, form, concept”—we don’t escape this trap; we’re still “focusing on the qualities of the commodity,” not, Taeyoung argues, “its participation within an ecology of social relations and politics.”

What, then, might result if space was “seen for what it actually FEELS, SUPPORTS, CREATES between people?” What would an architecture that focused “on social systems, politics, emotions, proxemics” look like?

Taeyoung suggests that a student (or teacher) of architecture could learn from the recent George Floyd protests, specifically the autonomous spaces organized under the #abolitionplaza or #OccupyCityHall hashtags. These spaces, of course, follow in the footsteps of Occupy Wall Street, an event foundational to Taeyoung’s thinking:

In researching the history of people’s occupations while writing this newsletter this week, I also turned up an even earlier antecedent, which I hadn’t been familiar with previously: 1968’s “Resurrection City,” a Washington DC settlement organized by Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as part of the Poor People’s Campaign. Photographer George Tames captured hundreds of images of the settlement, but most went unpublished until 2017, when they were included in Unseen: Unpublished Black History From the New York Times Archives:

Thinking about architecture focused on “social systems,” reminded me of a note in my card index, from 2000, directing me to investigate the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. Fathy—according to my note—worked “to revive traditional methods of production […] in order to create a social ecology in which traditional ways of life could thrive without Western influence.”

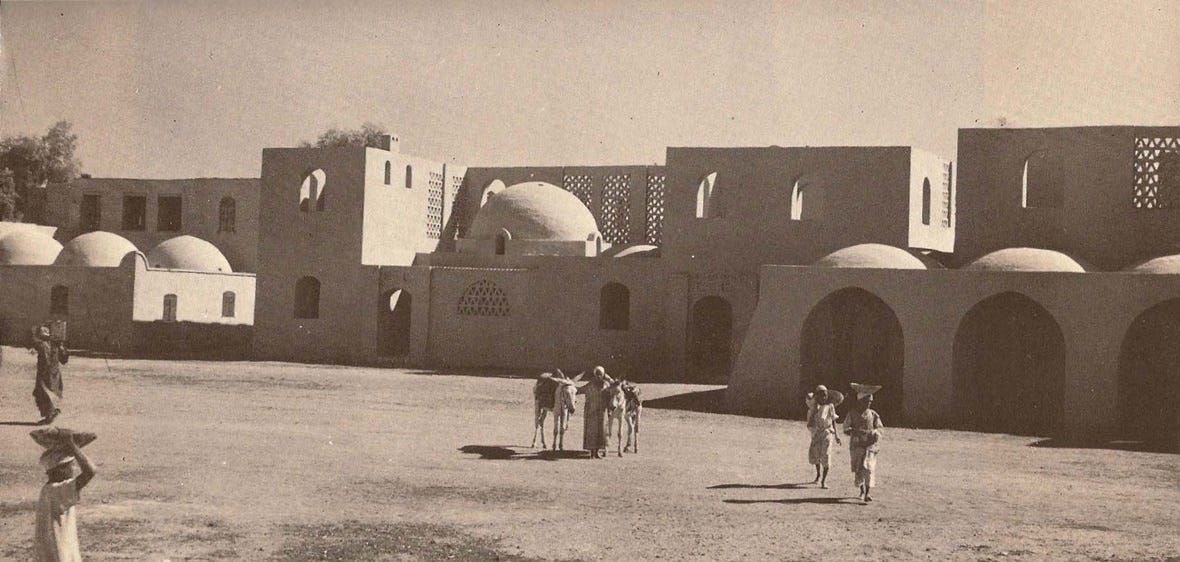

Fathy’s Wikipedia page was a bit of a mess—I rewrote some of it as I worked on this newsletter—so instead I turned to Fathy’s 1973 book Architecture for the Poor: An Experiment in Rural Egypt (originally published in 1969 as Gourna: A Tale of Two Villages). The book documents Fathy’s plan for building the village of New Gourna, a plan which included the use of what has come to be known as appropriate technology—notably mud brick construction—and traditional architectural designs (enclosed courtyards; vaulted roofing) and ornamental techniques (claustra, a form of mud latticework).

This passes muster from a “fine art” approach, because it yields significant aesthetic appeal:

It cannot help being beautiful, for the structure dictates the shapes and the material imposes the scale, every line respects the distribution of stresses, and the building takes on a satisfying and natural shape. Within the limits imposed by the resistance of materials—mud—and by the laws of statics, the architect finds himself suddenly free to shape space with his building, to enclose a volume of chaotic air and to bring it down to order and meaning to the scale of man, so that in his house at last there is no need of decoration put on afterward. The structural elements themselves provide unending interest for the eye.

But it also has the advantage of allowing us to escape the cult of “newness” that Taeyoung decries, and redirects emphasis away from superstar architect-auteurs. Hassan explicitly criticizes the “selfish appetite for fame” that he notes among architects, encouraging us to reconceptualize architecture as a field that benefits from time-honored repetition and careful iteration:

Architecture is still one of the most traditional arts. A work of architecture is meant to be used, its form is largely determined by precedent, and it is set before the public where they must look at it every day. The architect should respect the work of his predecessors and the public sensibility by not using his architecture as a medium of personal advertisement. Indeed, no architect can avoid using the work of earlier architects; however hard he strains after originality, by far the larger part of his work will be in some tradition or other.

Hassan also attempts to consider architecture’s operation in the realm of “social systems.” Noting that the traditional village, although impacted by overcrowding and sanitation issues, was also an expression of “a living society in all its complexity,” Fathy strived to design New Gourna in a manner that respected this complexity. Although Fathy attempted to implement some top-down measures—engineering some vocational retraining and meal programs—he also sought out the input of residents, and advocated for enlisting social ethnographers into the urban planning process. Perhaps more to Taeyoung’s point about what architecture can create “between people,” Hassan indicated clearly that he considered the project to be a “communal adventure,” an enterprise of “cooperative work”:

Indeed, the communal adventure of building a village by cooperative work should raise the morale, the self-respect, of the society, and give it a sense of common purpose that will be of immense spiritual benefit to its members.

Ultimately, this type of project is best understood not as aesthetic, but as political. Taeyoung advances this view in a piece examining the concept of “collective intelligence” (a concept advanced by Pierre Levy). Taeyong concludes this piece by stating that

Creating collective physical spaces is also, ultimately, a political act. To collectively shape space is to collectively shape our own ways of thinking and doing. Through shared spaces, we can change the way we think to be more collective, more open to change, more socially generous. Or, in other words, if we get used to changing the spaces around us, we can also become more adept at changing political and social realities.

A few links to round this out: for my money, the best thing ever written about #OccupyWallStreet remains Quinn Norton’s “A Eulogy for Occupy,” published at WIRED in 2012. Norton captures the radical aspects of spaces like the Occupy camps—the libraries, the shrines, the “multitudes of amazing people”—without turning a blind eye to the flaws, the abuse, the broken processes, the “parasites and predators.”

And we would do well to remember, of course, that any attempt to change the political and social reality of a space, if sufficiently radical, will inevitably encounter resistance from the police (or potentially the military). This point has been made repeatedly in the summer of 2020—the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest, or CHOP, might be just one example—but if you needed to round out your knowledge with a cinematic dramatization I’d recommend Gillo Pontecorvo’s excellent 1966 film The Battle of Algiers. A few years ago I made a collection of screenshots of “disputed spaces” found in the film: they feel as relevant as ever.

-JPB, writing from Turners Falls, MA, Tuesday, July 14 (revised Wednesday, July 15)

PS: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org—an online bookstore with a mission "to financially support local, independent bookstores"—and I maintain a list of books referenced in this newsletter. FTC rules advise me to disclose that I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

The Battle of Algiers is one of those films I try to foist upon everyone I know sooner or later. Folks tend to be snippy about the runtime in the post-Weinstein "ninety minutes and out" world, but that hasn't stopped me yet.