Wednesday Investigations 2.0 [005]: Brand new // you're retro

Looking forward to 2023; looking back to 1981, 1972, and 1966

So recently I was doing some Christmas shopping at The Million Year Picnic, a venerable Cambridge-area comic book shop, and although I did buy at least two gifts there, I also picked up something for myself: Alex Ross’ Fantastic Four: Full Circle, published this past September.

Ross has done painterly work for both Marvel and DC over the past 30-odd years—some of you may recognize his name from his work on the prestige retrospective Marvels (1994) or from DC’s apocalyptic opus Kingdom Come (1996). Anyway, he’s been around, and I’ve always appreciated how his work sits squarely at the juncture between the grandiose and the kitschy.

Full Circle, in my estimation, looks great:

It also marks Alex Ross’ writing debut. (Although he concocted the idea for Kingdom Come and wrote a lengthy outline for it, the credited writer is DC veteran Mark Waid.)

This is the part where I have to explain that I can be a little touchy about how people approach the Fantastic Four. As a team, they’re important to me—the first Marvel Universe comic I ever read was Fantastic Four #235, which I picked up off a newsstand in Oct 1981 (when I was nine years old). I quickly got a home subscription to the title, which I maintained for five years—so the team really serves as the central pillar in my early comics fandom. This is part of why I have Strong Nerd Opinions about how they should be written.

To be clear, I also had home subscriptions to The Uncanny X-Men and Marvel Team-Up (essentially a Spider-Man book). But in some ways my Strong Nerd Opinions feel less strongly held when dealing with Spider-Man or the X-Men, in part because over the years there have been a lot of great treatments of those characters, both in the comic books and in other media as well. So I know those characters can support various interesting interpretations!

Specifically: I grew up on Chris Claremont’s X-Men, which many consider the gold standard of writing on the book, but there are any number of smart, interesting runs in recent memory: Jonathan Hickman’s retooling of the entire line in 2019 is most notable here, but look back just a bit earlier and you find Matt Fraction’s run, or Grant Morrison’s, or even Joss Whedon’s. Similarly, Roger Stern’s 1980s work on Amazing Spider-Man is widely acclaimed, but I wouldn’t care to lose, say, Brian Bendis’ wholesale reinvention of the mythos in Ultimate Spider-Man. And this is before you even start talking about the films (I’m a fan of the X-Men as they appear in Logan (2017), for instance, and of the various Spider-figures as they appear in Into the Spider-Verse (2018)).

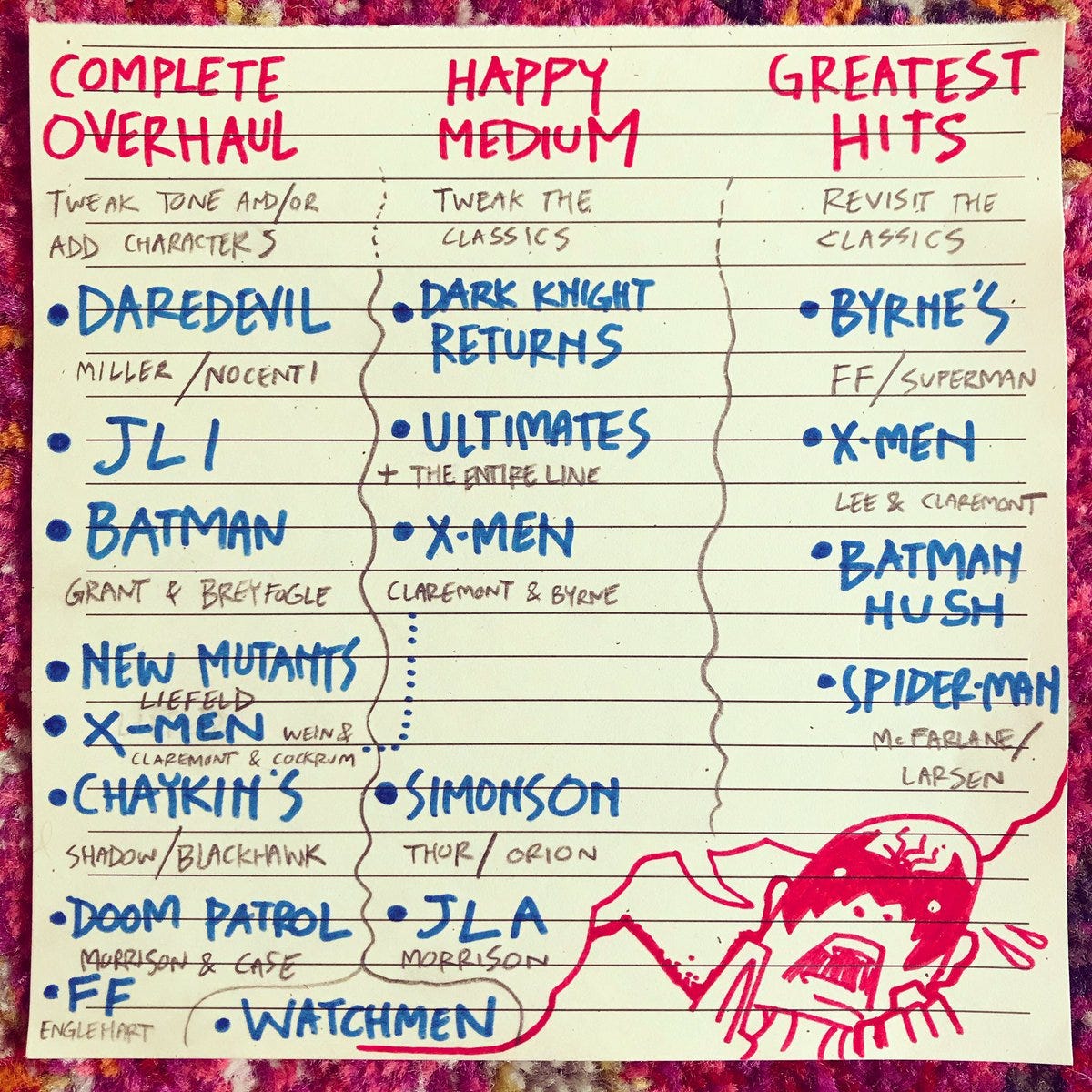

But the Fantastic Four have had fewer people at their helm over the years. The template for their adventures was set in an epic 101-issue run by the titanic creative team of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby (by contrast, Stan Lee wrote only 19 issues of Uncanny X-Men). My own foundational years in the comic were during John Byrne’s run, a 60-issue run which remains highly regarded, but primarily because Byrne adhered very closely to the Lee/Kirby template. Note it over in the “Greatest Hits” column there:

The Lee/Kirby/Byrne template is now so “fixed” in my mind that when people attempt to break from it—to modernize the characters in some way or another—it feels tonally wrong. With one major exception, about which more later, there have been few new Fantastic Four runs in the modern age of comics that people widely point to as successful; for two and a half years this decade there was no ongoing Fantastic Four title at all. (It’s back now, in the hands of Ryan North, who some of you may know from his work on The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl or his beloved dinosaur webcomic, which continues to this day.) And the existing Fantastic Four films are notoriously dire, with at least one being produced in about three weeks, primarily to extend a licensing option. (It was never released.)

The difficulty with adhering to the Lee/Byrne scripting template, though, is that… neither Lee nor Byrne is actually a terrific writer. Their template essentially involves ripping goofy cosmic conceits ripped from (B-grade) science fiction, and handling them with (equally B-grade) doses of straight-faced, self-important exposition. Leaven this with corny jokes and light bits of sitcom-adjacent banter, and you got yourself a Fantastic Four adventure! Most of this, however, isn’t palatable to an audience of contemporary readers, so you wind up in a bit of a jam.

Ross, rather admirably hits the mark here, getting out of the jam by framing the whole project as a bit of retro fun, which also allows him to hit the scripting notes “correctly” while also leaning into a trippy 60s-era visual quality, a suitable homage to Kirby’s own mindbending artwork from that era. The end result feels like stiff, square early-1960s astronauts staring wide-eyed into the delirious blacklight-poster bloom of late-1960s psychedelic experience—and that’s exactly what the Fantastic Four should feel like.

So… is era pastiche the only way forward for the Fantastic Four? Hard to say. (It may be notable that the forthcoming MCU Fantastic Four film (2025) is now being helmed by director Matt Shakman, best known for his work on WandaVision, a… pretty effective set of era pastiches?

There might be one writer who could show us a different way forward: specifically, Jonathan Hickman, whose work with the team (around 60 issues across a few different titles) is generally considered some of the best work in modern years, setting the stage for Hickman’s acclaimed runs on Avengers, New Avengers, and his canon-reshaping “event comic” Secret Wars. I can be lukewarm on Hickman’s work—even his work on the X-Men, which I praised above, had elements of what I see as Hickman’s overindulgence in technical junk. But I should probably get familiar with his Fantastic Four work to bolster my Strong Nerd Opinions. It’s on the slate for 2023 reading.

I kept a reading log this year, as I usually do. I’m currently at about 65 books for the year, which feels respectable. But I do feel a bit estranged from “literature” right now: there are fewer novels and nonfiction books on my list this year, and more collections of comics, more RPG rulebooks, more strange art books, etc. Some of the literature I did read feels a bit like I’m wandering through some dead zones and terminal points: books written by GPT-3, weary books about the impossibility of completing books, spent autofiction set in the scorched ruins of the capitalist brand-building industry, Madeline Gins’ career-long rejection of writing as a source of meaning, Rosaire Appel’s literally incomprehensible short stories. Lots of interesting stuff here, but very little of it seems to illuminate a promising future direction that literature might take. I’d be curious to know what you’re hoping to read next year, or what you read this year that seems to open up potential rather than chronicle the ways that potential can be shut down or negated.

The White Review just released their annual Books of the Year list; this usually points the way toward some exciting books to read; consider giving it a look.

What else am I looking forward to in 2023? Shin Ultraman is screening in the US for two nights in January:

Ultraman is a television show produced in Japan in 1966 featuring a Kyodai hero doing battle with kaiju; dubbed versions made it into US televsion market in the 1970s (full episodes can be found here). I was mesmerized by this show as a very young human, and Shin Ultraman—like the superb Shin Godzilla (2016) before it—looks very much like it will be a piece of work that will tune in unerringly to the retro elements that make Ultraman feel “right” to a [cough] aging demographic who might have fond memories of the 60s version. Jan 11!

Then, on Jan 13, I’ll be catching a screening of Skinamarink, a terrifying-looking bit of microbudget horror.

Skinamarink is also retro in its orientation: the (disturbing!) trailer derives much of its uncanny aesthetic from a near-fetishistic attention to period fonts, dirty film grain, and uneven tape warble. It draws explicit attention to this, literally showing the year of release as “1972” before that numeral glitches away to be replaced by “2022.” Is this a plot hint, or just a knowing nod to fellow period obsessives? Will this film dig into traumas from 50 years ago rearing their ugly head in the present? Who knows. I can tell you I’ll go see it!

Also possibly relevant here: VICE piece on “How the 20-Year Trend Cycle Collapsed,” which touches pointedly on the current efflorescence of multiple incompatible obsessions with cultural artifacts of the past.

See you in 2023.

—JPB, writing from Chicago, IL, in the week ending Wednesday, December 21

I had no idea until I read this that the dinosaur Ryan North was the same as the squirrel Ryan North.