Wednesday Investigations [2.7]: Inarticulate, disorderly, and magnificent

The sublime, the abject, Chicago noise music, and 18,000 stuffed animals

Let the record show that I was using the word “sublime” before I really knew what it meant.

Digging around in my notecard index, I realize that it wasn’t until around 2016, when reading Elaine Scarry’s book On Beauty and Being Just, that I even fully grasped where the category of “the sublime” came from—the writings of Kant and Edward Burke, who used it as a way to subdivide the aesthetic realm into two categories, specifically the “sublime” and the “beautiful.” Scarry criticizes this intellectual move, as she feels like it creates an oppositional (and gendered!) binary, in which the (masculine) “sublime” is given priority over the (feminine) “beautiful.” So, yeah, if you ever noticed that it feels like you might be running up against restrictive gender programming to say that a man is “beautiful,” or that art made by a man is “beautiful,” you can blame Kant and Burke for that, maybe?

OK fine. But… what even is “the sublime” again?

It would take me another two years to really nail it down. In 2018, I was reading this great essay on, of all things, Minecraft, written by Will Wiles. Wiles is a pretty interesting writer; although he publishes in the UK, I was able to find two of his early novels available through the US-based Bookshop.org: Care of Wooden Floors, described as being “about a man driven mad by a friend’s minimalist apartment” and The Way Inn, a “cosmic horror set in a mid-budget business hotel.” (He also has two more recent novels, Plume and The Last Blade Priest; not sure if these are available in the US.)

Anyway, in his essay, Wiles analyzes Minecraft convincingly as being committed to an aesthetic of the sublime, and to define the sublime he quotes Rosalind Williams (a historian who “uses imaginative literature as a source of evidence and insight into the history of technology”). She has a bunch of books in her own right, including one on the topic of “real and imagined undergrounds”: she discusses that topic at length in this interesting interview, at Cabinet.

Williams’ summary of Burke’s sublime claims that it encompasses the following:

“power, deprivation, vacuity, solitude, silence, great dimensions (particularly vastness in depth), infinity, magnificence, and finally obscurity (because mystery and uncertainty arouse awe and dread). … the open ocean, the starry heavens, inarticulate cries of man or beast. Above all, darkness[.]”

Helpful! But at the start of this newsletter I confessed that I might have been slinging the word around before I really had a great grip on it. It’s true: dig deep enough into the depths of the Internet and you can find me in the Chicago Reader talking about something I call the “New Electronic Sublime,” all the way back in 2006. I’m using this term there as a shorthand for a particular kind of “heavy drone” music, “electrically charged[,] with a lot of distortion.” Even though this is twelve years before Williams’ summation of Burke’s aesthetic made it into my notecard index, I’m not too embarrassed by my usage. I’m being a little pretentious, sure, but in my defense I had the concept basically correct: fans of loud, noisy drone music will tell you that it does, in fact, evoke an aesthetic of infinity and magnificence, or a sense of massive dimensionality, or a sense of oceanic vastness, or distant galaxies; when vocals come in they’re not far from the “inarticulate cries of man or beast.”

Scarry’s observation of the gendered sublime, then, might explain why the “drone scene,” such as it is, can so often feel like a boy’s club. Though, like any attempt to separate things clearly into a binary system, the idea that “the sublime is masculine” begins to strain under close scrutiny. Like—if you were to indulge in the dubious practice of sorting symbolic aesthetic material into essentialized gender categories, would you treat “the open ocean” as masculine because of its Romantic surging and grand smashing, or would you treat it as feminine because of its tidal pulls and its amniotic slosh?

Or take some other terms from Williams’ list—deprivation, solitude, mystery, uncertainty, “inarticulate cries.” It’s not a stretch to say that a lot of these terms could be associated with “abjection”—Julia Kristeva’s concept—which people smarter than me have sometimes linked to a kind of “monstrous feminine.”

If you need a good definition of the abject, and who doesn’t these days, my notecard index has this: “that which ‘disturbs’ categories of order and identity, a thing which negates and opposes and fascinates.” Hilariously, this is from another essay on video games, Silent Hill 2 this time, by horror writer Astrid Anne Rose.

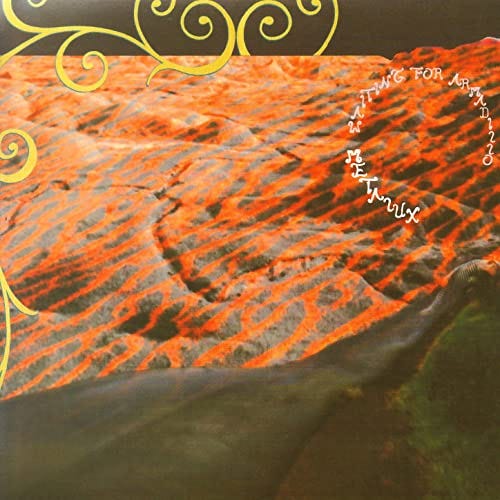

I’ll set aside the tangled question of whether “the disturbing of categories” can itself be categorized as a “feminine” enterprise. I will say, though, that the reason I was reflecting back on my 2006 musings on the sublime in the first place is because I was recalling some caustic and indeed very sublime performances by women I saw around that time, specifically some from Metalux, the Chicago noise project of M.V. Carbon and J. Graf. Check out their 2004 release Waiting for Armadillo (released on the sadly defunct Load Records) and wherever you may stand on how/whether to gender these categories, I think we can agree that this release stands as a demonstration of both the sublime and the abject by any measure. It’s powerful, mysterious, inarticulate, disorderly, magnificent: it is approaching its 20-year anniversary and it still “negates and opposes and fascinates” as profoundly as it did then.

Graf and Carbon have since left Chicago (Graf went to Baltimore, Carbon to Brooklyn), and Metalux’s last release, as far as I am aware, was over a decade ago (that was 2011’s Paw the Elated Ruin—oh yeah, ruins are also sublime, in case you hadn’t heard.) I’m not sure what Graf is up to these days, but Carbon still releases work on occasion, including an extremely scuzzy collaboration with Old Electronic Sublime violinist Tony Conrad (RIP) dating back to 2008 and, most recently, a collaboration with the avant-garde pianist Charlemagne Palestine. That was released just this week—inspiring this newsletter entry—though I’ve been waiting for it to drop since 2018!

More sublime artwork:

Anyway, this release is good and you should check it out. Charlemagne Palestine is a great weirdo in his own right, worthy of a whole separate newsletter, not least because he has a vast collection of stuffed animals, which he arranges around his piano when he performs:

In addition to his important piano compositions, he’s also channeled his weirdness into art installations; I was sad to miss this show in 2018 (I was on the wrong coast) which featured about 18,000 stuffed animals, though an expanded edition of the show catalog may be available at some point (for about 40 Euros).

Or, for 56 Euros (sigh), I could score Charlemagne Palestine: Sacred Bordello, which, if I have this right, contains an essay by cartoonist and WIRE contributor Edwin Pouncey explaining part of what Palestine is up to with those stuffed animals. I haven’t read this essay, but somehow I got a quote from it into the note index. Here’s Palestine:

“[W]hen I look at these [stuffed] animals for a certain period of time, they seem to present themselves in this inanimate, but animated world of sponges and magnets. Like a sunflower, when the sun shines they open up, and by doing so they reveal who they are. They become characters in this strange, continuous theatre of inanimate animism… They absorb a certain kind of energy and then they transmit it into the other space.”

Sponges and magnets! The inanimate but animated world! A strange and continuous theatre! Sublime.

Ruin Lust, a Tate Britain show co-curated by Brian Dillon, scholar of sublime ruins. Aside from this, he is also the author of Suppose A Sentence, a book devoted to the “oblique and complex pleasures of the sentence.”

Related: Ingrid Burrington, who some have described as “the premier infrastructure writer in America,” has a newsletter about “perfect sentences” that you should check out. Every newsletter, including this one, could benefit from an occasional “check out this sentence” feature.

Here’s a list of drone music by women, assembled by the great Justin Snow.

-JPB, writing from Dedham, MA and the Roslindale neighborhood of Boston, in the week ending Wednesday, January 11