Wednesday Investigation 13: Beth Anderson, Lily Greenham, a. rawlings: intermedia poetic production

In a previous edition of this newsletter, en route to talking about the work of the Japanese architect Toyo Ito, I wrote about the thinky essays you used to find in CD liner booklets. As you may remember, I’m an avowed admirer of writing in that genre, and even though the genre is probably vanishing it nonetheless pleases me to report that one thing I wrote professionally this year was, lo and behold, my own thinky essay in a CD liner booklet!

In this little piece, “Anagrammatic Paradise,” written for the stalwart Bay Area experimental music organization / label Other Minds, I consider the work of the artist and composer Beth Anderson. Anderson’s work resists easy characterization—each track on the album is a piece of sound poetry, based on someone’s name, but the sound poems themselves grow out of anagrammatic processes worked out on a grid. Here’s a shot, courtesy of Anderson, for track 38, “Meredith Monk”:

You could appreciate these grids as a form of visual poetry—they remind me of Jackson Mac Low’s “Gathas”—which complicates the question of which domain Anderson’s work “truly” fits within. I ended up deciding that this question was, honestly, a red herring: that slotting it too neatly within one domain or another was, ultimately, to miss the point. Not just the point, but also much of the pleasure: Anderson’s work asks you to watch as a unit of meaning, someone’s name, gets run through processes that belong to different creative domains; she wants you to delight in seeing the slippages that occur as meaning gets translated from one form to another.

As I was figuring this out, I had a little help from Fluxus artist Dick Higgins, who championed the concept of intermedia as a way to categorize artworks that cross boundaries between domains in this precise way. Especially helpful was Higgins’ “Intermedia Map,” which attempts to literally provide a cartographic visualization of areas where the most fruitfully permeable boundaries might lie. (It’s reprinted in Siglio’s anthology of Higgins’ work, Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press.)

I was introduced to Anderson’s work (and, in fact, tapped to write the liner essay) by my friend Andrew Weathers, the Recordings Director for Other Music. (He also runs his own label, Full Spectrum Records, and is a remarkable genre-crossing musician in his own right, recording music that ranges from traditionals from the American folkbook to longform ambient dreamscapes to autobiographical Auto-Tuned spoken word pieces about California irrigation and dental care.)

Anyway, back in December of last year, Andrew spotted me on Twitter casting about for information about women working at the blurry outer borders of experimental poetry. Twitter gets knocked, not entirely unfairly, for contributing to an inhumane cultural dialogue (it’s been that way, I’d argue, ever since it was weaponized during the #Gamergate days), but despite all that I find that it can still be a great place for people to come together and share resources. On that day in December, Andrew and Coffee House Press publisher Chris Fischbach directed me to David Menestres and Trisha Low (whose book Socialist Realism looks worth checking out), and thanks to their help I emerged with a notecard directing me to investigate a remarkable set of women working in intermedia poetics, specifically those who use sound or performance in their work.

Here’s the list, as I recorded it: Lily Greenham, Maggie O’Sullivan, Arleen Schloss, Tracie Morris, Holly Melgard, Holly Pester, and a rawlings. Taken together, these women represent an enormous range of productive activity spanning nearly a century. Lily Greenham was born in 1924; by the 1960s she had begun to make her way through a formidable sequence of European art scenes (Vienna, Copenhagen, Paris, Madrid Lisbon, and, finally, London); she died in 2001. Arleen Schloss emerged in New York City during the Downtown loft scene of the 1970s and 80s; Tracie Morris came up through the Lower East Side poetry scene in the early 1990s (she won the Nuyorican Grand Slam in 1993). Holly Melgard’s micropress, Troll Thread, blossomed in the hothouse of 2010s-era Tumblr; a rawlings’ dissertation, Performing Geochronology in the Anthropocene: Multiple Temporalities of North Atlantic Foreshores, made it online as a PDF as recently as 31 days ago.

Let’s take a look at that dissertation for a second. Based on its title, we might seem to have strayed pretty far afield from poetics—where are we now, in… the sciences? (The term “anthropocene” comes maybe from a chemist, and maybe from a biologist, and its adoption is currently under consideration by a team of geologists and paleobiologists, so you could be forgiven for thinking so.) But, well, guess again: rawlings’ PhD is from the University of Glasgow’s School of Culture & Creative Arts, and much of what the dissertation explores is the theoretical underpinning of rawlings’ richly weird ecologically minded intermedia poetics. Specifically, it is built around a series of “performance scores” collected in rawlings’ 2019 book Sound of Mull (published, incidentally, by an organization with a delightfully boundary-crossing name in its own right: Labae—the Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology.) (An ebook is also available.)

A representative performance piece unpacked in the diss might be Intime (first performed in 2016). The Intime performance is described as a “shoreline interaction,” inspired in part by Pauline Oliveros’ “Deep Listening” events, involving choreographed circular movement, vocal improvisation, beachcombing, and “an audio recorder, obscured by seaweed.” The invitation to one iteration of Intime notes that the event

may spur participants to explore estrangement, intimacy, rural ritual, and/or relationship with human and more-than-human bodies. The interaction may be considered geopoetics performance-as-research. There will be ears, and the shore will be a room.

Looks wonderful to me. But if it raises more questions than answers about how to “perform geochronology in the Anthropocene,” well, there’s also this:

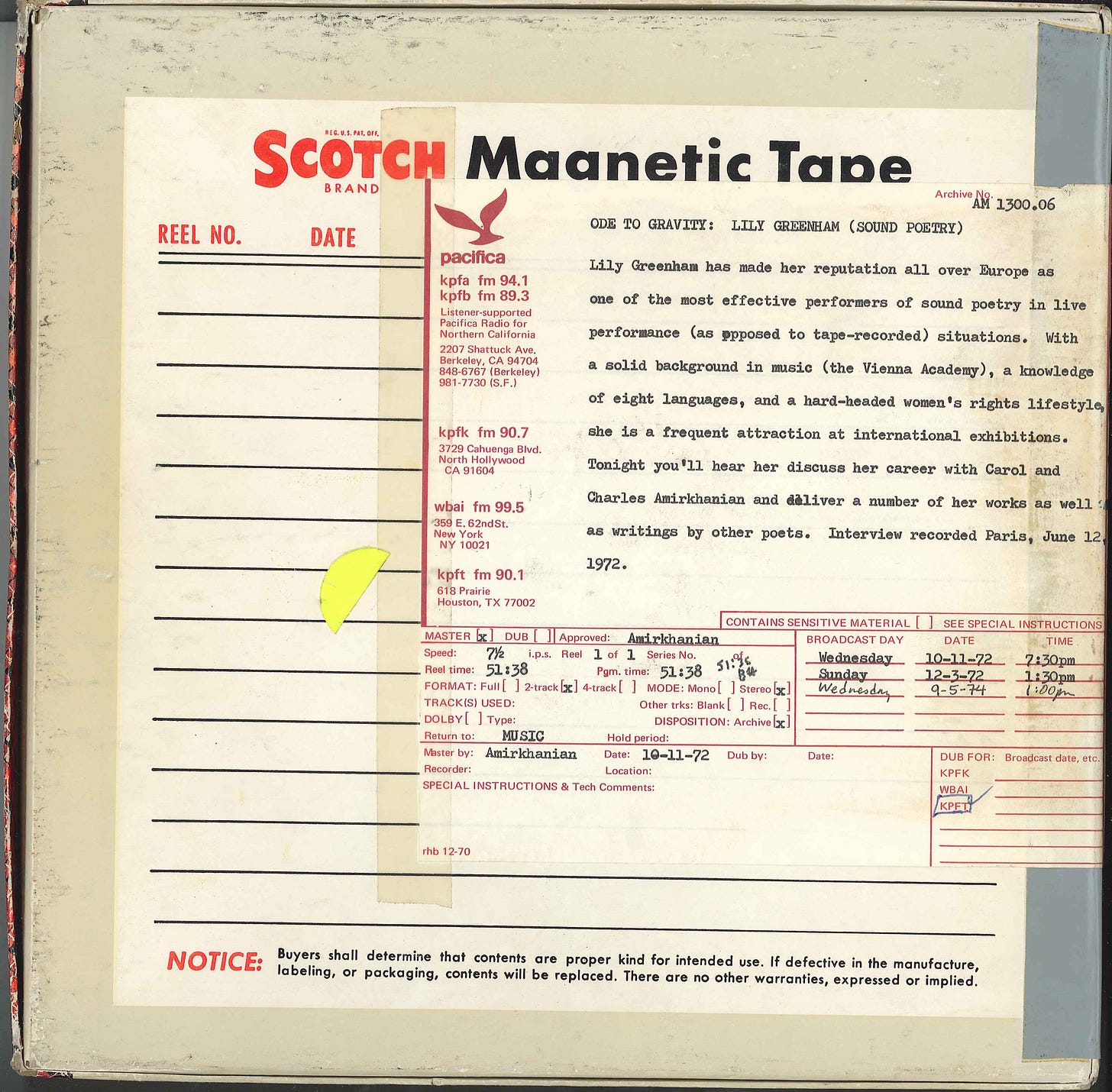

In this meditation rawling asks us, again and again, to reflect upon time and our place in it, which eventually lands me back to the overview of the hundred years spanned by the lives of the women in my note. One hundred years: a relatively small span, when viewed from a geological epochal perspective, but still much too long for me to do justice to it in a single edition of this newsletter. (More to investigate later.) For today, we’ll close out by returning to Lily Greenham, born 1924. Probably the world’s first female avant-garde sound poet, fluent in eight languages, and she doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page (I will try to fix that). But thanks to the Internet Archive, you can still listen to a remarkable 1971 episode of the KPFA radio program Ode to Gravity, where you can hear Greenham discuss her important work, and perform many of her pieces in her own voice.

She’s interviewed by Ode to Gravity host Charles Amirkhanian, who, as it happens, is now the Executive Director of Other Minds.

Beth Anderson’s Namely will be released by Other Minds on August 7.

-JPB // Dedham, MA, July 21, 2020 (revised Wednesday, July 22)