Wednesday Investigation 15: The "post-post apocalypse"

On "societies functioning after ruin," Twine texts, queer RPGs, and teaching about utopia in 2020

In two weeks, the fall semester will begin, and I’ll start teaching again.

The school where I teach, Northeastern University, committed to holding in-person classes way back in May, and unlike some other universities (UNC Chapel Hill comes to mind), they haven’t yet changed course. If anything, they’ve doubled down: our university president, Joseph Aoun, wrote a “why campuses need to reopen” editorial for the Washington Post just over a week ago; he’s also apparently slated to write a book on the topic, a “vivid account of how his school managed the COVID crisis,” to be entitled We Will Remain. Whether you find this title inspirational or queasy-making is probably a decent measure of your attitude toward the ongoing pandemic overall in this particular moment. I will only point out the obvious by adding that a claim that “we will remain” has the potential to prove premature: Northeastern’s already detected four positive cases among the university community, according to their COVID tracking dashboard. (Admittedly, that’s only a 0.05% positive rate, considerably better than Massachusetts’ own remarkably good 1.1% rate, but one does wonder just how much this is a harbinger of things to come as more students begin to flow in.)

One thing Northeastern has done well, though, is demonstrate flexibility. They committed to a hybrid arrangement that allows for a fluctuating mixture of in-person and remote instruction, with each student permitted the luxury of choice regarding how often they want to be in the physical classroom, and how often they want to participate via videoconferencing technology. Importantly, this same courtesy is extended to the instructors, even though this may lead to some odd arrangements, such as one in which there are students physically in the classroom, but the instructor is participating remotely.

Odd arrangements for odd times. As things currently stand, I’m planning to spend the whole semester teaching from home. I’m disappointed that the pandemic isn’t under control enough for me to feel comfortable returning to the classroom in person, but I’m keeping a hopeful eye on the… spring of 2021?

In any case, I really am looking forward to my courses this semester, even if the arrangement will be different than what I’m accustomed to. I’ve been reworking my pedagogy, dramatically in some cases, and I’ll be teaching a brand new course, on the topic of utopias. (Utopian thinking has been a recurrent theme of this newsletter, and some of the figures who have appeared in previous editions will be making cameos in the course, including Charles Fourier.)

Just yesterday, in my syllabus-in-progress for this class, I wrote that 2020 confronts us with many challenges, but it “also provides us with a unique opportunity for utopian thinking. The COVID-19 pandemic invites us to think about the way that our existing systems have failed to care for the most vulnerable; the ongoing unrest in response to police brutality invites us to think about the way our existing systems serve oppressive ends. In both cases, we have the opportunity—or even the responsibility—to collectively imagine ways in which things could be better.”

Selecting books that perform some of this work has been rewarding. I’ve chosen three: Eric Holthaus’ speculative work of climate optimism, The Future Earth; Trisha Low’s memoir of idealistic resistance, Socialist Realism (referenced briefly in this newsletter a few weeks ago); and Ursula K. LeGuin’s classic “ambiguous utopia,” The Dispossessed.

I cast a wide net this summer for other materials, and at one point I came upon a tweet from narrative designer Meghna Jayanth. In this tweet, Jayanth asks people to share their favorite works of “post-post apocalypse,” pieces of speculative fiction that depict “functioning societies after ruin.” A “functioning society” might look utopian when you’re trapped in a broken system, but isn’t exactly a utopia—at least not necessarily—so I ended up hesitating to pull anything from the replies to use in my course, but I did mark those replies for further investigation, which brings us to today.

A handful of things mentioned are exceedingly well-known: for instance, there’s Pendleton Ward’s cartoon Adventure Time (which takes place not in a mythical fantasyland but rather on an Earth recovering from nuclear war), which ran for ten seasons; there’s also Walter M. Miller Jr.’s science fiction novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, which has remained in print continuously since 1959. (I haven’t read Canticle, and I’ve only seen a few episodes of Adventure Time, although I am enjoying Ward’s new project, The Midnight Gospel: the best mix of loopy animation and stoner philosophizing since Richard Linklater’s Waking Life (2001).)

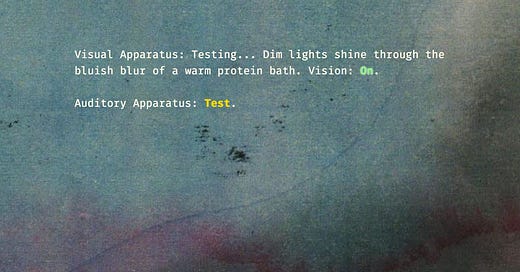

I could have investigated either of those a little more deeply, but it was the lesser-known items in the assortment that I found especially intriguing. Given that Jayanth is an author of interactive fiction—she wrote the iOS piece 80 Days, generally considered one of the most successful interactive fiction works of the past decade—it should not surprise us to see other works from that genre well represented in these replies. Someone plugs Floatpoint (by the notable IF writer/programmer Emily Short) describing it as a “biopunk” tale “about a space colony that moves out of communication range, and then back in after a few decades, and what happens after that.” Short joins the thread not long after, to recommend Jedediah Berry’s Twine piece Fabricationist DeWit Remakes the World, in which you play as an entity revived from stasis and set to work on a Great Project of a restorative bent (Short’s write-up of the piece can be found here.)

A “Twine piece,” for those of you who don’t know, is a work made using the hypertext engine Twine, a tool developed in 2009. Twine is notable for its ease of use (it requires no programming experience), and as a result, it found widespread adoption by an array of marginalized people who might otherwise have been walled out of the game design community, especially queer and trans game creators. Many had chalked up hypertext storytelling as a creative dead end after an initial flurry of interest in the 1990s: even longtime advocates of the form, such as myself, were surprised to see this new flourishing of hypertext games on nontraditional topics. Some of the delectable ferment of the 2010s Twine scene has been documented for posterity in a hefty tome called Videogames for Humans: Twine Authors in Conversation.

You might expect to a book about video game designers to be published by a tech-focused university press like MIT Press (they’re the ones slated to publish Aoun’s We Will Remain, just incidentally). It is perhaps testimony to the marginal nature of the Twine scene that this book is instead published by the small, transgressive press Instar Books, taking a rightful place alongside anthologies of trans erotica and novels where the protagonist makes money by jacking off for strangers on the internet. (This isn’t their only “tech” book, though: they also published the complete output of Allison Parrish’s @everyword bot as a book, including “accurate counts of the number of times each was favorited and retweeted by Twitter users”.)

If you want some taste of the Twine scene but don’t feel quite ready to commit to a 575-page book on the topic, take literally just ten seconds and play this unexpectedly moving game about “queers at the end of the world”.

Thinking about queers at the end of the world leads us back to the post-post-apocalypse recommendations. The final recommendation I investigated today is one for Avery Adler’s Dream Askew, a tabletop role-playing game in which you play members of a queer enclave, attempting to build a community against a backdrop of ongoing social collapse.

Some of you might know Adler from her mapmaking game The Quiet Year, which also focuses on developing a community after the collapse of civilization; others of you might know her from her influential game Monsterhearts, which draws on tropes from cultural texts like Buffy and Twilight to allow players to tell stories about “sexy monsters, teenage angst, personal horror, and secret love triangles.”

Dream Askew is made using a role-playing game framework called Belonging Outside Belonging, developed by Adler in collaboration with Benjamin Rosenblum (designer of Dream Apart, published in the same volume as Dream Askew). Belonging Outside Belonging-powered games are collaborative games that eschew the normal trappings of role-playing games (the use of dice, the deference to a “game master”) in order to better facilitate the telling of stories about “hopeful, precarious, vulnerable” people; stories “about what happens when marginalized groups establish their own communities, just outside or hidden within the boundaries of a dominant culture.” (Here’s a series of podcast interviews with a number of different game designers working with the Belonging Outside Belonging system, if you’re interested in learning more.)

In setting the stage for how these dynamics play out in Dream Askew, Adler writes:

Imagine that the collapse of civilization didn’t happen everywhere at the same time. Instead, it’s happening in waves. Every day, more people fall out of the society intact. We queers were always living in the margins of that society, finding solidarity, love, and meaning in the strangest of places.

[…]

We banded together to form a queer enclave — a place to live, sleep, and hopefully heal. More than ever before, each of us is responsible for the survival and fate of our community. What lies in the rubble? For this close-knit group of queers, could it be utopia?

It’s a little too late for me to include this game in my class, which is a bit of a shame—about a week ago I was out there explicitly looking for queer utopian texts, and this would have filled that gap quite nicely—but I’m also maintaining an Are.na channel for supplementary materials on the topic of utopia, and I’ll be sure to post this game to that channel. (Students might be able to spot it there, as I’ll be sharing my channel with them, and I’ll be having them maintain their own Are.na channels as well.)

Are.na, in case you aren’t familiar, is a “visual organization tool” built by artists, designers, and creative entrepreneurs, and it emphasizes mindfulness, focus, and collaboration in its “value proposition.” It is ad-free, provides no mechanism for “likes,” provides no algorithmically-recommended content, and does not sell information about you to third parties. In these ways and others, it presents its own sort of utopian vision by suggesting a world in which tech companies could be more humane and ethical.

-JPB, Dedham, MA, June 26, 2020