Wednesday Investigations [2.12]: Jay Owens

Talking particles, places, and psychogeography with the author of "Dust"

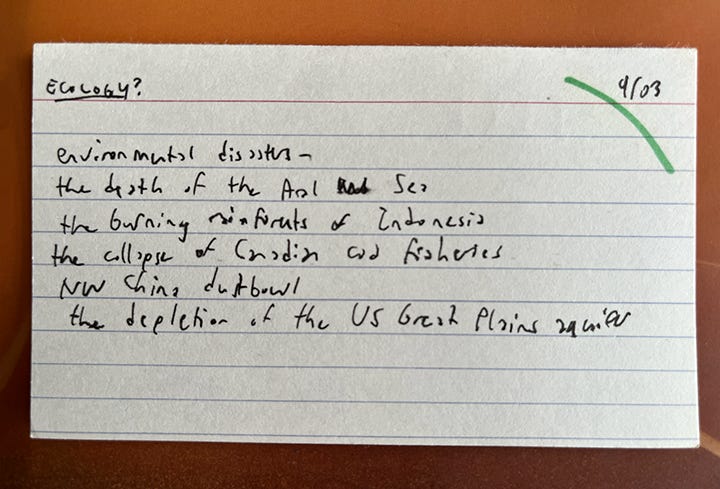

The oldest note about dust in my card index is from 2003, which I regret to inform you is now twenty-one years ago. It’s a note listing some major environmental disasters, including the rapid expansion of the Gobi Desert, driven by human-led deforestation and overgrazing. It appears here as the “NW China dustbowl.”

Also on this list is the “death of the Aral Sea,” a lake that bordered Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan before the water that fills it was diverted by Stalin-era Soviet irrigation projects, designed to improve cotton yields.

As it happens, the death of the Aral Sea is not just the death of an ecosystem, but it is also a second disaster involving dust. You see, the Aral Sea was a type of lake known as an endorheic lake—a lake without an outlet. Because whatever washes into endoheric lakes can’t easily be flushed back out, they tend to collect salt (the Great Salt Lake, which is also drying up, is also endoheric). Unfortunately, these types of lakes also collect pollutants, such as pesticides from agricultural runoff. So when the Aral Sea evaporated, it created the Aralkum Desert, the youngest desert in the world, a desert comprised of salt and poison. A landscape of toxic dust, easily carried by the wind. Health outcomes in the region have declined so precipitously that some refer to it as the “slow Chernobyl.”

Clearly, we can learn a lot by “thinking with dust.” Not everything we learn is bad: part of the reason the Amazon is so fertile is because dust clouds replenish phosphorous that might otherwise be washed out by the heavy rainfalls. And some of what we learn is just plain weird: like, it’s hard to really know what dust is. The dust under your couch might be microscopic bits of hair and skin, sure, but it’s probably also at least partly bits of the couch itself, disintegrated bits of foam and fiber. That dust could also contain myriad other particles: carbon from cooking in your kitchen, for instance, or stuff tracked in from outside—mineral dust, pollen, road dust (including microplastics from crumbling tires). There could even be a particle of bomb-test uranium in there, which, if it happens to be in the wrong place when it decays, could kill you.

Dust is commonplace, yet cryptic. It’s unseemly, unhygienic, dangerous, sometimes deadly—yet oddly intriguing. It’s uncanny, a subject of uneasy fascination—which, to the right kind of mind, makes it irresistible.

Jay Owens has been my guide to “thinking with dust” for some time now. She began a newsletter about dust, “Disturbances,” in 2016, to which I was an avid subscriber. When I learned that she was working on a book: Dust: The Modern World in a Trillion Particles, I was elated. The book was released late last year, to widespread acclaim. Robin Sloan describes it as “a book that uses its very specific subject as a lever to crack open the megascale, the universal, even the sublime […] a globetrotting odyssey that touches science, nature, and geopolitics. [O]ne reason to read this book, among many, might be the provocation it suggests: what kind of project might YOU begin, that could conceivably take you to places this wild, and result in a piece of work this formidable?”

Owens’ book takes you to the Gobi Desert and the Aral Sea, but also to raves and reservoirs, homes and hospitals. Comprised of eyewitness accounts, interviews, and old-fashioned library research, it represents a titanic investigative achievement, and comes with my strong recommendation.

I interviewed Owens on January 23.

JPB: Your bio on Instagram begins “hiker writer researcher,” and although I am eager to talk about your writing and researching, I thought it was notable that you listed “hiker” first. Is the basis for that chronological? Were you a hiker before you were a writer and a researcher?

Jay Owens: Biographically, yes—but hiking, or otherwise getting out into places and landscapes, is also important to me as process for the writing.

As a kid, I was dragged up mountains by my father, a keen hillwalker, but I wasn't necessarily a huge fan: it was raining (it's always raining in the Lake District), my feet hurt, I'd slipped over in some sheep poo, et cetera. I started walking properly when I was 22 and studying for a Masters degree in London. I needed a holiday but I had no money—but I could get a train up to Cumbria for £50, and stay in youth hostels for about £10, and pack my own lunches and walk all day (free)...

And I loved it — the freedom, the physical challenge, the sense of being present in the landscape, in the moment, thinking only about where you are, and where next to put your feet.

I started writing seriously in 2015, spurred by travel—by a roadtrip with friends into the deserts of California and Nevada. The places we went were extraordinary and radically new to me, and I just wanted to tell people about them, and the experience of travelling through them—which I did first in Instagram captions, then Medium posts, and then my Disturbances newsletter.

Since then, that sense of experiencing place has been the thing I write from. There's a certain amount of open road in that (US 395 in California, in particular)—but yes, as much time on foot as I can.

I have some fond memories of hiking out in the UK, going to see tor formations allegedly of importance to the druids.

I was really struck, at that time, by the fact that I could walk on privately owned land thanks to “right to roam” law in the UK. We don’t have the equivalent of that here in the US—my memories of traveling here, like yours, are about roadtrips rather than foot-trips. Regardless, is there a hike—either in the UK or far from home—that stands out as especially memorable to you? A particular portion of the Cumbrian Way you want to recommend?

Now that's a question! Let me pull up the maps...

Oh, good.

Two, perhaps:

1. Crinkle Crags and Bow Fell from Langdale one December—the first snowfall of the season. Up Oxendale, down via Angle Tarn (which is in fact a small segment of the Cumbrian Way). Champagne air, blue skies, and hiking downhill through two feet of pure powder, post-holing up to the thighs - and then pints and whiskies by the fire of the Britannia Inn in Elterwater. The best winter mountain day I've ever had.

2. Secondly, a hike I did on New Year's Day in 2015: the Cactus to Clouds route up San Jacinto Peak in Palm Springs. It's about 20 miles and 10,300 feet (3,100 m) in elevation gain—vertically speaking, it's the biggest single-day route in the mainland US. We set off at 01:30 in the morning and finished mid-afternoon, starting in a desert cactus garden and finishing in snow and pine forest - through a scarlet sunrise that ranks, still, as the most extraordinary I've ever seen. It wasn't until we headed down the mountain via the cable car that I really appreciated the height - the ride just goes on and on, and you realise you've just climbed all that. It made me realise I could do big things. I don't think I could have written the book without having done that first.

Yes, there’s certainly a lot of “experience of place” in Dust!

There are lots of ways you could describe the book—it's part cultural anthropology and part ecological history—but seen a certain way you could also say that it's an adventure story. If nothing else, it is certainly globe-trotting—it takes you to from the Mojave Desert to the Ilulissat icefjord in Greenland, with a side trip out to a rave in Western Uzbekistan. These are “big things,” as you put it, not simple trips—do you feel like “adventure” is the right descriptor?

We don’t use the word “adventurer” much in the 21st century; I imagine this is because it carries some echo of colonial-era narratives that our culture is in the perhaps overdue process of reconsidering. But if we could set the colonialist baggage of the term aside, do you feel the label “adventurer” applies to you?

Heh, “adventurer” is a degree less loaded than calling oneself an “explorer”—but not a term I'd quite use myself. I take some interesting trips, but not at quite the degree of physical exertion that might justify the title. If I were doing 100km off-trail hiking routes or bike touring or packrafting in the Arctic, Central Asia etc, then sure. But I haven't done that—or not yet, at least.

There's a British guy—Alastair Humphreys—who very much is that sort of epic adventurer: he's rowed the Atlantic, cycled the world and so on. But he's developed a nice line in talking about 'microadventures' too, the journeys you can take at much smaller scale or much closer at home that nonetheless feed our senses of curiosity, play and discovery. I think that's a good way of thinking about the world, too.

Iain Sinclair walking the London ring roads comes to mind.

Yes! I think Humphreys did that too. His latest book Local: A Search for Nearby Nature and Wildness entails exploring every gridsquare of your local Ordinance Survey map—which are typically 1:25,000 scale.

I am... not sure I can be that excited about North London—I have tried! I had to, during lockdowns in 2020 and 2021. But my heart is elsewhere.

That puts me in mind of William Least Heat-Moon, who did a version of that for Kansas with his epic PrairyErth book, which I once described as the rare book of "American psychogeography."

Oh I don't know his work—looks super interesting, but I better not go down Wikipedia rabbitholes for a bit!

Is there a place that you would have liked to go for Dust that you wanted to see, but couldn’t? If you had extra time, extra money, or extra access, is there one more place you would have traveled?

God, what a great question.

I would sell my soul to the devil to spend a summer on the Greenland ice cap with a glaciology field camp. (If the British Antarctic Survey are reading, I feel the same way about the southern polar regions too, just FYI and please and thank you...) The ice sheets are the most otherworldly place on this planet, and a landscape of extreme contrast: dazzling blue crevasses and moulins against filthy brown dust and meltwater. I would love to spend some significant time with the ice, to get to know it a little–while working alongside the scientists who are measuring its past and forecasting its future. It wouldn't be an easy experience–the awe would shade into shock, and loss, and horror. But it would mean the world to do so.

The other place I couldn't go was western and northwestern China—the Gobi and the Taklamakan deserts are the second biggest mineral dust sources on the planet after the Sahara. But the country was closed for covid—and meanwhile, China commits atrocities against its Uighur minority. To go there and look at dust would be missing the forest for the trees.

A lot of what Dust documents is not just travel, of course. You go to places, but then you talk to experts or other interesting guides who help to make sense of those places. I lost count midway through—how many interviews would you say you conducted for the book?

I think about twenty, give or take—which is actually fewer than writers coming from, say, a New Yorker longform journalism tradition might do for a work of that length.

I don't use interviews for factual information, mostly—I mostly did them only once I'd done all my other research. Interviews are for asking people what it all means and why it matters - and getting the quotes that express what's at stake better than I ever could.

I showed the book to my students, and they were cheerfully aghast when I showed them that there were nearly forty pages of cited sources at the back.

I'm sorry, students! Yes, I think about 500 sources after I'd edited the endnotes down.

Every single endnote goes back to the original source–not news articles or derivative publications—which is nerdy but hopefully useful for anyone who might come to use the book in their own research in future.

I spent weeks tracking down a story Rebecca Solnit told but didn't cite about horses having their eyes blown out by nuclear testing in Nevada.

That's just not a sentence you hear very often.

The image was a guiding metaphor for that chapter: I wanted to explore the paradox of early above-ground nuclear testing as both hypervisible ‘atomic spectacle’ (cc. viewing parties in Las Vegas, and so on) but also a massive coverup—in which many many people engaged in a kind of ‘willful blindness’ as to the actual risks involved.

But then she doesn't cite... And I'm like, I can't use that as hearsay, I'm not that sort of writer.

You did find it, if I recall.

I did! Footnote 21, pg. 368. "Vincent, Bill 1984, ‘Mine Strafed, Bombed By Air Force’, attributed to Western Sportsman newspaper August 1984 (I believe actually Western Outdoors: The Magazine for the Western Sportsman)—accessed via p. 134 of United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, 1987, ‘Land Withdrawals from the Public Domain for Military Purposes’, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Lands, Reserved Water and Resource Conservation, 99th Congress Second Session on S. 2412 a Bill to Withdraw and Reserve Certain Public Lands, 17 July 1986 (available online)."

Amazing. This is my kind of citation.

This is my gift to future writers!

Terrific.

Thank you to public records-keepers, digitisers and archivists everywhere, of course. 🙏

Their work was particularly essential given I was largely writing and researching remotely, during a pandemic—though I'd have the same problems now, given that the British Library's information systems have been down for months due to a ransomware attack. (Have you heard this?)

Yeah, I have!

They're having to rebuild major systems from the bottom up, it seems—wild.

I'd like to begin to wrap up, but I want to quickly pivot first. From your social media presence I know you also have an interest in fashion and beauty. These topics don’t come to the forefront of Dust: we get the beauty of the natural world, at times, but beauty or glamor in an anthropological or sociological sense is sort of outside the scope of the book. (There's one possible exception, which I'll discuss in a moment.) This interest does appear more prominently, perhaps, in Disturbances—you write about the manufactured allure of the iPhone, for instance. But is there a piece of your writing that you’d hold up, though, as being “the one” where you really explore that domain of human expression?

So, yes, the other side of my writing. I'm massively interested in fashion but actually haven't written about it directly—instead, I'd say the other side of my interests coalesce around digital cultures and how we live online.

Two favourite pieces there—'TELL ME, DO YOU INTEND TO FUCK IT?' as you mention (published in Dirty Furniture magazine, 2021)—and 'My Friend, The Bot' from 2016.

Though the latter has succumbed to linkrot, as Botaleptic, the subject of the story, has been deleted from Twitter.

Elon killed my art bots, which I was very sad (read: angry) about.

It is very sad about the bots!

Is it a different sort of writing? Perhaps not, perhaps not—it's all still place-writing. I've always felt—always known—that online worlds are places too, and the presence you have in those spaces is as real as anything offline.

Nothing virtual about the experience.

I mentioned an “exception”above and wanted to swing back to it: it's the section of Dust where you talk about the Uzbekistan music festival.

Hah! Possibly the most polarising part of the book—my editor loved it, the Sunday Times reviewer not so much.

That's the part of the book where you talk the most about what people are wearing, for instance: be it young girls in bikini tops, or the DJ’s black T-shirt dress, or the organizer’s incongruous preppy Hilfiger shirt, or the pairs of false eyelashes that you packed for the trip. This might just be scene-setting detail, but I did feel like I was being led across the dance floor by someone attuned to it as a performative space, a space where fashion, beauty, or glamor matters. You use the word “presence,” and the floor of a club is certainly a place where presence is foregrounded.

You know, you're the first person who's said anything about the function of fashion in that chapter—I hadn't realised I'd written like that until you pointed it out just now! But you're entirely right.

Clothes are a language in which we figure out the kinds of people we want to be—it's perhaps not a coincidence I've been thinking about them particularly intensively this last week while I've been recovering from foot surgery. They're part of imagining what I want to do out in the world again, once I have that freedom back.

In that section, you note that you feel somewhat estranged from a generation of up-and-coming young people, both at home in London and beyond, who missed out on a certain era of club culture, and don’t “know or care about the things a dance floor can do.” Do you want to talk about revelations you’ve had on the dance floor? Do you still find yourself interpreting those spaces through a sociological or anthropological lens when you’re in the moment, or does the analytical part of your brain take a break? When you were talking about hiking you said you enjoyed the sensation of “thinking only about where you are”—is that true, for you, in a club environment?

Between this foot injury, a pandemic and general encroaching old age, I really haven't been dancing enough in recent years. (I've been loving writing from Michelle Lhooq, who has a newsletter called 'Rave New World'—and also Mackenzie Wark's 2023 book Raving).

But yes, I'm not a heavily analytical clubgoer. I'm interested in what people are wearing and how they move, the general fluid dynamics of crowds and how DJs can play them like an instrument.

But if you're doing it right then yes, it's a space of presence and present-tense mindedness. I'm not thinking too hard, if at all.

As an aging music lover myself, I got a lot of melancholy enjoyment out of V/VM's Death of Rave project.

Though I did somehow find myself in a mosh pit in 2023; that was a pleasant surprise.

Nice! Very envious of that! That's a project for when my foot is better, for sure.

On top of everything else, you’re also now the Director of Audience for the London Review of Books—a place where I imagine your interest in digital culture can fully flower.

I have joined the media industry at an interesting time (it is always an interesting time in the media). My job is to get people to read the LRB online, but we are at the very end of one media era—the social media era of abundant Facebook traffic and buoyant Twitter discourse—and entering into a new one, the contours of which aren't entirely clear. It's something about email and loyalty and subscriptions, everyone reckons—and I think that's about right—but figuring out the right levers to press in this new system, the gearing of a new machine, is fascinating. I'm having a lot of fun (and the numbers are indeed going up).

If there's anything else you'd like to recommend—any current reading, or a show you're watching on the couch as you recover?

Oh my taste in television certainly isn't worth publicising! I'll watch any thriller/action/spy nonsense going...

I'm excited to read Systems Ultra: Making Sense of Technology in a Complex World by Georgina Voss, which is out today—alongside working through the stack of doomy environmental books I've brought home from the office, whose titles really are quite a lot—there's Sad Planets by Dominic Pettman and Eugene Thacker, The City of Tomorrow is a Dying Thing by Des Fitzgerald, The Weight of Nature by Clayton Aldern— and On Extinction, by Ben Ware.

I also picked up a copy of Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country by Louise Erdrich, which might counteract the white-guy eco-misery, let’s see. (Who has the luxury of mourning? Not everyone.)

Oh yes! I saw that Georgina Voss’ book was available. I saw someone post your book, Georgina’s book, and Deb Chachra’s How Infrastructure Works all together, and I really do think all three will pair perfectly.

Very much so!

OK, well—thank you for your time!

This has been great, thank you so much for the invitation.

Dust: The Modern World in a Trillion Particles is available wherever books are sold1.

—JPB, writing from Boston, MA in the week ending Wednesday, January 24

I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org—an online bookstore with a mission "to financially support local, independent bookstores"—and I maintain a list of books referenced in this newsletter. FTC rules advise me to disclose that I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.